Safeguarding Children and Young People from Sexual Exploitation

Scope of this chapter

Missing from Care Procedure & Protocols - to follow

Internet and Mobile Phone Safety Procedure - to follow

Regulations and Standards

Quality and Purpose of Care Standard – Regulation 6

Engaging with the wider system to ensure children’s needs are met – Regulation 5

The Protection of Children Standard – Regulation 12

Leadership and Management Standard – Regulation 13

PRACTICE GUIDANCE AND TOOLS

- Hounslow’s Child Sexual exploitation workflow;

- Hounslow’s Missing from home workflow;

- Hounslow’s Children missing from care work flow;

- ‘The Real Story’ Resource pack for CSE. Barnardo’s;

- Growing up, sex and relationships; A guide to support parents of young disabled people: Contact a family;

- Growing up, sex and relationships: A guide for young disable people: Contact a Family;

- Healthy Relationship workbook: Theresa Fears MSW, The Partnership 4 Safety Program.

Related guidance

- The London Child Sexual Exploitation Operating Protocol

- Female Genital Mutilation - Standard Operating Procedure

- London Safeguarding Children Procedures, Referral and Assessment Procedure

- London Safeguarding Children Procedures, Allegations Against Staff or Volunteers (People in Positions of Trust), who Work with Children Procedure

- Hounslow LADO Protocol

- The London Child Sexual Exploitation Operating Protocol, 3rd Edition June 2017;

- Under protected, Overprotected: Meeting the needs of young people with learning disabilities who experience or are at risk of, sexual exploitation Anita Franklin, Phil Raws and Emilie Smeaton, September 2015 (Barnardo’s)

- Inquiry into Child Sexual Exploitation in Gangs and Groups (CSEGG), Children’s Commissioner, 2012

- Tackling Child Sexual Exploitation Action Plan, Department for Education, 2011

- Child sexual exploitation: definition and guide for practitioners

- Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre (CEOP)

- Tackling child exploitation and extra-familial harm – new Practice Principles to support professionals

- The role of protective parenting assessments and interventions in the prevention of child sexual abuse - Information from the Lucy Faithfull Foundation on how parents and carers can protect their children from sexual harm

Amendment

This chapter was refreshed in May 2025.

CSE is a form of child sexual abuse that affects both boys and girls. Sexual abuse may involve physical contact, including assault by penetration (e.g. rape or oral sex) or non-penetrative acts such as masturbation, kissing, rubbing and touching outside clothing. It may include non-contact activities, such as involving children in the production of sexual images, forcing children to look at sexual images or watch sexual activities, encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways, or grooming a child in preparation for abuse (including via the internet).

The definition of child sexual exploitation is as follows:

‘Child sexual exploitation is a form of child sexual abuse. It occurs where an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity (a) in exchange for something the victim needs or wants, and/or (b) for the financial advantage or increased status of the perpetrator or facilitator. The victim may have been sexually exploited even if the sexual activity appears consensual. Child sexual exploitation does not always involve physical contact; it can also occur through the use of technology.’

(Department of Education, February 2017.)

Sexually exploited young people rarely approach the police or social workers directly and disclose that they are being exploited. It is a shared responsibility for all to identify young people vulnerable to, at risk of, or experiencing CSE. It is important that everyone working with young people are aware of the vulnerabilities and risk indicators that can make a young person more vulnerable.

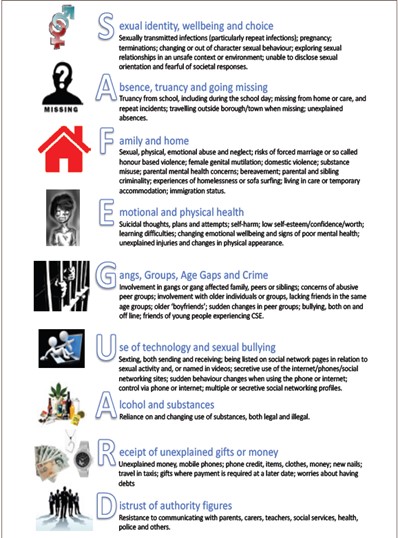

To assist all practitioners in identifying and remembering the signs, the mnemonic S.A.F.E.G.U.A.R.D.

- There is a general lack of learning and knowledge pertaining to LD/SENCO children at risk or suffering from sexual exploitation, in the UK and internationally;

- There is a lack of statistical evidence pertaining to CSE and disability;

- There is interchangeable use of the terms ‘learning disabilities’, ‘learning difficulties’, ‘special needs’ and ‘intellectual impairments’. Definitional issues that stem from a lack of understanding of these terms and interchangeable use of these terms are noted as impacting on protecting these children;

- From research evidence on the abuse of disabled children, it can be identified that young people with learning disabilities are more at risk and are vulnerable to exploitation in general;

- There are identified issues around disclosure and the identification of abuse by professionals;

- Lack of preventative work through education, raising awareness of CSE and safety skills development;

- There is a lack of evidence gathered directly from young people with learning disabilities who have experienced CSE. Their views can assist in identifying the most effective ways to protect other children and young people.

Young people can be sexually exploited by people of a similar age as well as adults. Research is increasingly demonstrating that a significant number of sexually exploited young people have been abused by their peers and a London Councils report in 2014 found that peer-on-peer exploitation was the most frequently identified form of CSE in London. Young people can be exploited by their peers in a number of ways. In some cases, young women and young men who have been exploited themselves, by adults or peers, will recruit other young people to be abused. In other instances, sexual bullying in schools and other social settings can result in the sexual exploitation of young people by their peers. Sexual exploitation also occurs within and between street gangs, where sex is used in exchange for safety, protection, drugs and simply belonging. For 16 and 17-year-olds who are in abusive relationships, what may appear to be a case of domestic abuse may also involve sexual exploitation. In all cases of peer-on-peer exploitation, a power imbalance will still inform the relationship, but this inequality will not necessarily be the result of an age gap between the abuser and the abused.

Children and young people have grown up in a digital world which has improved people’s lives in many ways, such as giving us multiple methods to communicate and share information. It is a constantly changing and dynamic world that is now an essential part of a young person’s life. However, these freedoms also create new risks – according to the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre (CEOP), a significant number of CSE offences take place online. These offences include deceiving children into producing indecent images of themselves and engaging in sexual chat online or sexual activity over a webcam. Children and young people at risk of harm online may not have any previous vulnerabilities that are often associated with being victims of sexual abuse and exploitation. This means that they are less likely to be identified as they might not be previously known to the authorities. Due to the nature of online activity, the currently accepted indicators of possible sexual exploitation, such as going missing or school absence, may not be displayed, and the first parents may know that their child has been a victim of sexual exploitation is when the police contact the family. Children and young people often do not see the dangers of sharing intimate images of themselves to strangers. The internet creates a false feeling of security and diminishes inhibitions that would exist offline. The anonymous nature of the internet allows perpetrators to adopt false personas and build trust via online conversations. Children and young people can fail to realise that they lose control of uploaded images, falsely believing the properties of social media applications will protect them. This leads to risks of blackmail and coercion against the child. Additionally, the Global Positioning System coordinates of where a digital image was created can be identified using free-to-download software packages, potentially leading a perpetrator to a child. These factors can lead to any and all of the following risks:

- Online grooming and child abuse;

- Access to age-inappropriate content;

- Bullying and cyberbullying;

- Personal information being obtained by perpetrators; and

- Talking to strangers or people who misrepresent themselves.

Here the offender befriends and grooms a young person into a ‘relationship’ and then coerces or forces them to have sex with friends or associates. The abuser may be significantly older than the victim, but not always.

Sharing photos and videos online is part of daily life for many people, enabling them to share their experiences, connect with friends and record their lives. The increase in speed and ease of sharing imagery has led to concerns about young people creating and sharing sexual imagery of themselves. This can expose them to risks, particularly if the images are shared further, including embarrassment, bullying and an increased vulnerability to sexual exploitation. If a young person has shared imagery consensually, such as when in a romantic relationship or as a joke, or there is no intended malice, it is usually appropriate for the school to manage the incident internally. In contrast, any incident with aggravating factors, such as a young person sharing someone else’s imagery without consent and with malicious intent, should generally be referred to the police. The police must record and investigate these cases and this will result in seizure of devices and interviews with young people. Schools should confiscate devices if they suspect there is sexual imagery on them, but they should not view the images and instead accept what is being reported. Such devices should be turned off, secured and the police notified. The College of Policing published detailed guidance in November 2016 on police action in relation to youth-produced sexual imagery:

- Professionals need to respond in a proportionate way to reports of children (under 18-year-olds) possessing, sharing or generating indecent imagery of themselves or other children. This activity may constitute an indecent image offence and be illegal under the Protection of Children Act 1978 and Criminal Justice Act 1998.

- Most offences involving sexual activity with children will require a full criminal investigative response, e.g. in the presence of exploitation, coercion, a profit motive or adults as perpetrators. Offences involving self-generated images or images obtained with consent by other children may be dealt with differently. Forces may, for example, consider that suitably experienced first responders, safer school officers or neighbourhood teams can provide an appropriate response, thereby avoiding stigmatizing children or causing them unnecessary fears and concerns. For police purposes, the recently introduced ‘outcome 21’ provides for forces to resolve crimes with the appropriate contextual factors in a proportionate and effective way.

- In deciding whether criminal justice processes are necessary and proportionate, forces will wish to consider the long-term impact of investigation and prosecution, such as labelling a child a ‘sex offender’ and potential disclosure as part of a Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) process. Chief constables have discretion to consider whether behaviour covered in this paper should be disclosed on a DBS enhanced check, as for other non-conviction information.

- Police need to work with schools to educate children on the risks of exchanging imagery, to engage as appropriate during investigations, and understand schools’ powers to delete images. The link below provides further guidance in relation to these issues in education establishments.

County lines typically involve an inner-city criminal gang travelling to smaller locations to sell drugs. The group will use a single telephone number for customers ordering drugs, operated from outside the area, which becomes their ‘brand’. Unlike other criminal activities where telephone numbers are changed on a regular basis, these telephone numbers have value so are maintained and protected. The gangs tend to use a local property, generally belonging to a vulnerable person, as a base for their activities. This is often taken over by force or coercion, and in some instances victims have left their homes in fear of violence. Perpetrators employ various tactics to evade detection, including rotating gang members between locations so they are not identified by law enforcement or competitors, and using women and children to transport drugs in the belief that they are less likely to be stopped and searched.

CSE can also be seen in these types of cases and every effort should be taken to identify those young people that are also being sexually exploited as well as being coerced into other criminal behaviour. This could constitute an offence of trafficking either for sexual exploitation or criminal exploitation, and a crime report and National Referral Mechanism (NRM) referral should be made and investigated. These situations will often become apparent to professionals when young people are located after missing episodes outside the London area, where there is no apparent reason for them being in that location and having no apparent means to have travelled there.

Young people associated with gangs are at a high risk of sexual exploitation. Sexual violence among peers is commonplace and it is used as a means of power and control over others, most commonly young women. Young people affected by, or associated with, gangs are at high risk of sexual exploitation and violence, and require safeguarding. The Office of the Children’s Commissioner has defined CSE in gangs and groups in its 2013 report. This includes:

Gangs – mainly comprising men and boys aged 13 to 25, who take part in many forms of criminal activity (e.g. knife crime or robbery) who can engage in violence against other gangs, and who have identifiable markers, e.g. a territory, a name, or (sometimes) clothing.

Groups – involves people who come together in person or online for the purpose of setting up, coordinating and/or taking part in the sexual exploitation of children in either an organised or opportunistic way. Sexual exploitation is used in gangs to:

- Exert power and control over members;

- Initiate young people into the gang;

- Exchange sexual activity for status or protection;

- Entrap rival gang members by exploiting girls and young women; and

- Inflict sexual assault as a weapon in conflict.

Young people (often connected) are passed through networks, possibly over geographical distances, between towns and cities, where they may be forced/ coerced into sexual activity with multiple men. Often this occurs at ‘parties’ or brothels, and young people who are involved may recruit others into the network. Some of this activity is described as serious organised crime and can involve the organised ‘buying and selling’ of young people by offenders. Organised exploitation varies from spontaneous networking between groups of offenders, to more serious organised crime where young people are effectively ‘sold’. Children are known to be trafficked for sexual exploitation, and this can occur across and within local authority (LA) boundaries, regions and across international borders.

Children can be exploited by their parents and/or other family members. Parents or other family members may also arrange the abuse of the child and/ or control and facilitate exploitation. Where one child is being exploited, siblings or other child relatives are at increased risk of suffering exploitation.

This may occur quickly and without any form of grooming. Typically, older males identify vulnerable young people who may already have been groomed or sexually abused. The perpetrator will offer a young person a ‘reward’ or payment in exchange for sexual acts. The perpetrator is often linked with a network of abusive adults.

Staff in the home should be aware of the key indicators of child sexual exploitation. They include:

- Having a prior experience of neglect, physical and/or sexual abuse;

- Lack of a safe/stable home environment, now or in the past (e.g. domestic violence or parental substance misuse, mental health issues or criminality);

- Recent bereavement or loss;

- Social isolation or social difficulties;

- Absence of a safe environment to explore sexuality;

- Economic vulnerability;

- Missing from home or care;

- Gang association;

- Dependent on drugs and alcohol;

- Homelessness or insecure accommodation status;

- Connections with other children and young people who are being sexually exploited;

- Family members or other connections involved in adult sex work;

- Having a physical or learning disability;

- Being in care (particularly those in residential care and those with

- interrupted care histories); and

- Young people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or whose gender identify differs from the sex they were given at birth.

This list is not exhaustive.

- Going missing (return home interviews key);

- Presence of older men;

- Controlling adults;

- Physical injuries or symptoms (think psychosomatic);

- Attached to phone;

- Mood swings/sudden change in relationships (peer or familial);

- Being taken to flats/hotels/trap houses/ unknown car’s/ taxi’s everywhere;

- Engaging in sexual activities/ love, affection, sex, desire to be wanted;

- Taking drugs or abusing alcohol;

- Self-harming, suicide attempts;

- STI’s or STD’s unplanned pregnancies;

- Unexplained gifts, belongings, phones, money, drugs;

- Suddenly refusing to attend school not engaged in usual activities.

This list is not exhaustive.

Staff should be aware that many children and young people who are sexually exploited do not see themselves as victims. In such situations, discussions with them about staff concerns should be handled with great sensitivity. Best practice would advise that prior advice sought be sought from management and Hounslow’s Exploitation and Vulnerabilities Coordinator or specialist agencies. This should not involve disclosing personal, identifiable information at this stage.

In assessing whether a child or young person is a victim of sexual exploitation, or at risk, careful consideration should be given to the issue of consent. It is important to bear in mind that:

- A child under the age of 13 is not legally capable of consenting to sex (it is statutory rape) or any other type of sexual touching;

- Sexual activity with a child under 16 is an offence;

- It is an offence for a person to have a sexual relationship with a 16 or 17-year-old if they hold a position of trust or authority in relation to them;

- Where sexual activity with a 16 or 17-year-old does not result in an offence being committed, it may still result in harm, or the likelihood of harm being suffered;

- Non-consensual sex is rape whatever the age of the victim; and

- If the victim is incapacitated through drink or drugs, or the victim or his or her family has been subject to violence or the threat of it, they cannot be considered to have given true consent.

- Child sexual exploitation is therefore potentially a child protection issue for all children under the age of 18 years and not just those in a specific age group.

- The sharing of indecent photographs and videos of children under the age of 18 is an offence which workers have a duty to report to the police.

Professionals dealing with a disclosure or where there are indicators that a child/young person may feel able to make a disclosure, the worker must discuss this with their manager and if applicable seek guidance from the Exploitation and vulnerabilities Coordinator. It is essential that workers within the service seek guidance from Hounslow’s Child Sexual Exploitation Work Flow process.

A significant number of children and young people who are being sexually exploited may go missing from care and education, some frequently. If a child goes missing from home or care, the procedures stipulated within Hounslow’s;

- Missing from home workflow;

- Missing from care workflow.

For concerns pertaining to missing, seek consultation with Hounslow Children Service’s Exploitation and Vulnerabilities Coordinator. As well as responding to an individual child or young person who goes missing the home should also collate and share data on missing incidents. This should be discussed with local agencies involved in the strategic response in relation to missing children, to ascertain what data is required.

Missing children and young people may be at increased risk of CSE and should be reported as missing to police at the earliest opportunity. Once a missing child is located, it is important that they are properly debriefed to identify any risks the child has been exposed to. There are two stages to the process:

- The Police Prevention Interview (formerly known as the Safe and Well Check); and

- The Independent Return Home Interview.

Child sexual exploitation is a form of sexual abuse and needs to be reported to the police on the day the disclosure was made within or too the service. CSE is also a safeguarding issue that Children’s Services will need to assess and will need to be notified along with the police on the day of the disclosure. A referral to police should be via calling 999 or 101 (dependant on the incident) and a referral to Children’s Services MASH team will need to be undertaken in writing.

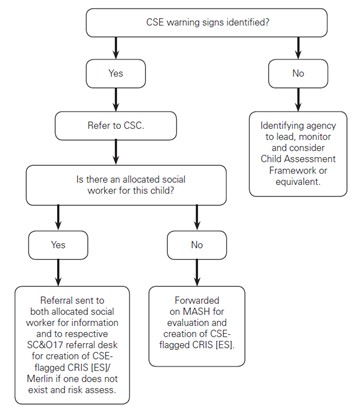

Where a member of staff is concerned that a child or young person is involved in, or at risk of, sexual exploitation, they should discuss their concerns with a senior member of staff or the home’s Designated Child Protection Manager. If it is decided that action needs to be taken to protect the child, local safeguarding procedures should be triggered (please refer to Hounslow’s Child Sexual Exploitation Referral Pathway workflow). This will include making a referral to children’s social care in which the home is located and the local police.

- When managing a disclosure, staff must also refer to the Child Protection Referrals Procedure, Reporting Concerns, Suspicions or Allegations of Abuse or Harm;

- In the case of suspected child sexual exploitation Ofsted, the placing authority and police must be informed (see also Consents and Delegated Authority Procedure);

- It may be helpful for workers to complete Hounslow’s CSE Risk Assessment Tool which will generate a risk indicator. All completed forms need to be held within the child’s files and sent to the Exploitation and Vulnerabilities Coordinator to file on their Children’s Services File.

If the child or young person is not deemed to be in need, the social worker should consider onward referral to relevant agencies. This should include liaison with the keyworker at the home.

The purpose of a MASE meeting is to have tactical oversight of CSE cases, information, intelligence and activity across each LA area and across borough boundaries. MASE should have the capacity to remove blockages or obstacles in cases, as well as considering and directing resources and activity in response to trends identified from those cases. It is recommended these meetings should be convened on a monthly basis or at a maximum of six-week intervals. The meetings should be jointly chaired by the Local Borough Police at Detective Chief Inspector (DCI) or Detective Inspector (DI) level and by a senior manager from CSC (Assistant Director Safeguarding and Quality Assurance or a service manager from Operational CSC are considered to be at the requisite level.)

In order to assist in the identification of themes and/or emerging trends, reports should be presented at the MASE meeting in a format that ensures the key information and intelligence is properly captured. It is recommended that MASE should consider this key information using the VOLT mnemonic.

V – Victim(s)

O – Offender(s)/perpetrators/

persons of concern

L – Location(s)

T – Theme(s)

If a young person attending Westbrook is assessed within Children’s Services as at risk of/or suffering from sexual exploitation, the service may be asked to support the actions that have been actioned at the Pre MASE to bolster safeguards around the child. The service may be asked to feedback to children’s services and/or the police on any indicators, patterns, themes, or concerns they have for the child pertaining to sexual exploitation.

Professional scrutiny should be applied to all cases where evidence of trafficking exists but the NRM has not been activated. MASE Panels should ensure cases of trafficking are correctly identified and that the appropriate responses are in put in place. This should in reports to the LSCB sub-groups (or equivalent). In addition, by measuring the activity against the four strands of Prepare, Protect, Prevent & Pursue, this will enable MASE to feed into and work in support of each borough’s Local CSE Action Plan. Each LSCB or equivalent should agree an outcomes framework and reporting process for MASE activity and measurement. It is recommended that, alongside the agreed data set, a narrative providing a contextual basis for the figures, together with thematic patterns/trends/concerns is provided. MASE could also consider implementing a process for reviewing case outcomes through audits/case studies.

Children suffering from some forms of disability or mental health illness and disorders may have episodes where they are assessed under the Mental Capacity Act 2005. If a young person over the age of 16 has sex however is assessed by law as having diminished capacity to engage in sexual activity, the police and children’s services will need to be notified to complete relevant checks and assessments of need and risk.

The fact that a young person is 16 or 17 years old and has reached the legal age of consent should not be taken to mean that they are no longer at risk of sexual exploitation. These young people are defined as children under the Children Act 1989 and 2004, and they can still suffer significant harm as a result of sexual exploitation. Their right to support and protection from harm should not, therefore, be ignored or downgraded by services because they are over the age of 16, or are no longer in mainstream education.

Sexual activity with a child under the age of 13 is an offence regardless of consent or the defendant’s belief of the child’s age.

The Act also provides for offences specifically to tackle the use of children in the sex industry, where a child is under 18

(S 47 to 50 Sexual offences Act).

Statutory agencies and voluntary sector organisations together with the child or young person, and his / her family as appropriate, should agree on the services which should be provided to them and how they will be coordinated. The types of intervention offered should be appropriate to their needs and should take full account of identified risk factors and their individual circumstances. Health services provided may include sexual health services and mental health services. If there is agreed consent a referral may be made on to specialist services for sexual exploitation. Within Hounslow, The Women and Girls Network and the NSPCC provide bespoke one to one direct work or work with schools on sexual exploitation.

The effect of sexual abuse and exploitation on child development. This should be incorporated into the young person’s Pathway Plan.

Ivison Trust

Ivison Trust helps parents to understand what is happening to their child and how parents can be the primary agents in helping their child disclose and break away from child sexual exploitation. Ivison Trust has a long history of working collaboratively with the police and social services and looks forward to further cooperation with more agencies. We offer training and guidance for best practice.

‘Let’s Talk PANTS’ NSPCC

PANTS are a free interactive tool kit which is used to help engage small children in to helpful discussions around sex, consent, privates and sexual abuse. This pack is free to order from the NSPCC and can be used by families and professionals alike.

Barnardo’s - Be Smart, Be Safe Resource Pack

This is an extremely helpful resource pack with six session plans broken down to help professionals engage, intervene and guide young people at risk or suffering from sexual exploitation. The sessions can be run on an individual or group setting and include interactive sessions and also sessions which advise to use short films also produced by Barnardo’s which support the theme of the session.

My body is mine – A colouring & read-with-me book for safety smart kids

With this book, children can learn safe boundaries, how to differentiate between “good” and “bad” touches, and how to respond appropriately to unwanted touches.

It also contains a ‘More Things that Parents Should Know’ section.

Last Updated: November 4, 2025

v32